UKRAINE’S MOST UKRAINIAN ARCHITECTURE

DAN MALITSKYY

What do we see when we look at Ukrainian cities?

Soviet modernism. Imperial classicism. French Renaissance facades. These styles (borrowed, imposed, adapted) form the urban face of Ukraine. But is there anything beneath them? Something unique; something unmistakably our own?

Ukrainian Architectural Modern (Ukrainian Art Nouveau or UAM) is that something. A style that prevailed briefly and brilliantly in the early 20th century. It is rooted in folk traditions and shaped by national aspiration and identity. Unfortunately, it is little known even within Ukraine. But it should be. These buildings do not merely stand – they tell a story. And what they say is both beautiful and indispensable.

Across Europe, the early 1900s were a time of stylistic rebellion. Art Nouveau, Secession, Jugendstil… each region invented its own modern identity, rejecting classical uniformity. In Ukraine, this artistic wave collided with a deeper current: the search for cultural sovereignty.

But what could a modern Ukrainian city look like? Not one made in the image of Paris or Vienna, but in the image of Ukraine itself. Not imitation, but reinterpretation. Not nostalgia, but transformation. Ukrainian Architectural Modern drew from the vernacular: countryside homes (haty) with thick white walls and thatched roofs, wooden churches with tiered silhouettes, and national art. These elements were not pasted on, they were woven into the logic of design. This was architecture grown from folklore.

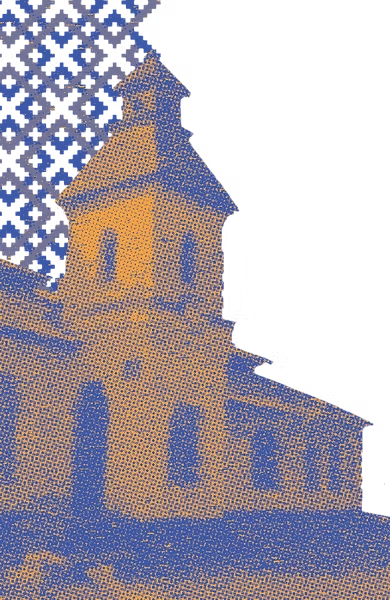

Across all these regions, a kind of architectural dialect began to form – a visual grammar of ‘Ukrainianness’ in a building. There were trapezoidal and hexagonal windows and doorways, their unconventional forms drawing the eye and being the most recognisable element in the style.

Semi-elliptical arches softened rigid geometries. Roofs often swelled into tented peaks or folded into tiered ridges, recalling mountain silhouettes. Wooden galleries stretched along facades, their pillars sometimes twisted into carved spirals.

Everywhere, tile and brick mosaics glimmered with patterns lifted from vyshyvanky, pysanky (decorated Easter eggs), and painted ceramics – fragments of a folk memory reassembled in clay and stone.

Unlike the palaces of empires, these buildings were filled with light and humility. Take, for instance, the rural schools designed by Opanas Slastion, where rooftop towers symbolised that ‘a school is a temple of knowledge,’ and brick ornamentation resembled woven embroidery (vyshyvanka).

Poltava, more than any other city, became the soul of this movement. Vasyl Krychevsky’s masterpiece, the Regional Studies Museum (formerly the Zemstvo Building), is often seen as the birth of the style. But the movement stretched far beyond: to Kyiv, to Kharkiv, to Chernihiv, even as far as Kuban.

UAM emerged at a time of radical social transformation. It lived through the collapse of the russian empire, World War I, Ukraine’s brief independence, and the rise of Bolshevism. In those short years, dozens of masterpieces were built. And then, suddenly, they were not.

What made UAM remarkable was not just its form, but its devotion to synthesis. Architecture became a vessel for the applied arts.

Ukrainian Architectural Modern is not just a historical curiosity. It is a testimony. It is the voice of great individuals who dared to speak and craft for Ukraine and Ukrainians.

It is also fragile. Fewer than a hundred significant buildings survive in relatively good condition. Some have been restored. Many are crumbling. And yet, each is a museum in itself – not only of objects and craftsmanship, but of ideas.

Look closer, ask questions, and remember. Because sometimes, the most powerful act of cultural memory is simply to notice.